The Swords, Sex, and Military Bureaucracy RPG of 1975

“What is this game?”

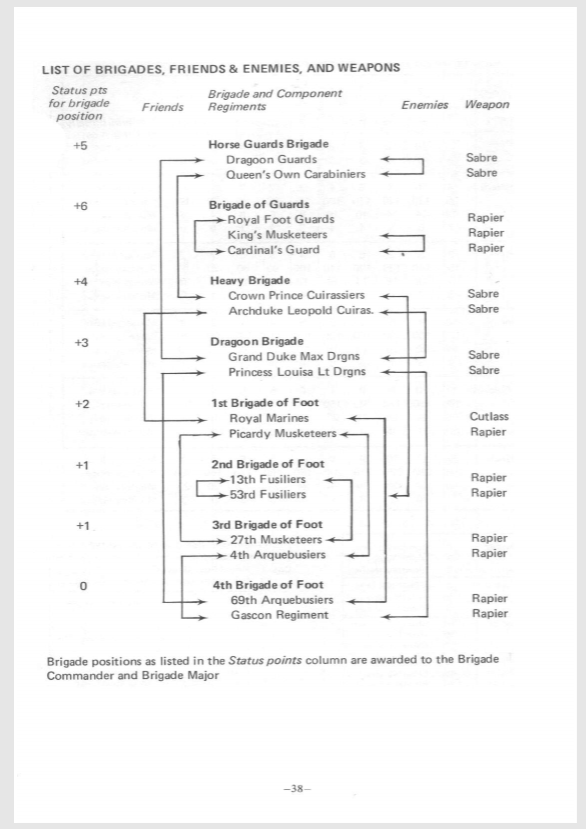

As my players seat themselves in the clubhouse, I deal each a crisp, blank index card.

“There,” I say. “That’ll be your character sheet. Save the back for your next character, after this one dies.”

The players cast an eye at my pencil-thick printed rulebook. “Is one side going to be enough?”

“Sure. Put your stats on the left and your birth circumstances on the right. If you want to name your character, put that at the top.”

“Wait, if?”

We’re getting ahead of ourselves. I flip to the front page of my printout and read verbatim from its introduction, originally published in 1975:

“En Garde! is a semi-historical game/simulation representing many of the situations of an Errol Flynn movie set in the Seventeenth or Eighteenth Centuries. The game was originally devised as a fencing system, with background added to provide scenarios for the duels.” I took a breath. “After a time, it became apparent that the background was more fun than the duels…”

I’m sorry to say this gets a laugh.

But you know, it probably shouldn’t. Right around the time this game was developed, a larger crew of gaming nerds was discovering that a system built for stabbing dragons in dungeons also produced stories more interesting than the sum of its raw mechanics.

But En Garde! is not like D&D. The reason I dusted it off to explore with my fellow RPG chrononauts is that it’s not much like any roleplaying game I’d heard of. It stands with Boot Hill, Tunnels and Trolls, and Empire of the Petal Throne as among the first (retroactively-defined) RPGs ever made, but in its goals and mechanics it is stranger than any one of them.

“You’ve got four stats,” I explain as the players take up the provided pencils and dice. “You’re going to roll 3d6 to calculate your Strength, Constitution, and Expertise. Now, multiply your Strength and Constitution. That’s basically your hit points.”

“Hold on, multiply?”

Phones come out, calculators calculate. One player has 182 Endurance; another, 72. “Sounds about right,” I say.

“So you’re telling us that in theory, we could roll as many as 324 hit points?”

“Or as few as, uh, 9. But what are the odds of that, right?” I thumb to the next section. “Now we’re going to roll your…background, birth order, and level of wealth. This will determine both your social status and your monthly income…”

“Hold on, what’s birth order?”

“How many sons are ahead of you to inherit titles and money.”

“So does the game actually allow you to play a female character?”

“To the creators, it was obvious you’d play a man. So they don’t spell it out. There is an explicit mechanic where you need ‘female company’ every month to avoid going down in social rank, so by the strictest literal interpretation you’re allowed to play anyone who macks on women.”

As anticipated, this is acceptable to all players present. The background rolling begins in earnest.

Through an amusing fluke, nearly all roll bastard status. None roll commoners. One player has an especially rarefied lineage:

“I’m illegitimate, but it looks like my father is a viscount. That’s really high status, right?”

“Yep!” I consult the complex social matrix pinned down in my rulebook. “Even though you’re a bastard, it looks like you’ll have far more clout than any character here.”

“Huh! So what does that actually mean?”

“You can get into one of the nicer social clubs, Hunter’s. You’ll also have an easier time courting high-status mistresses. However…it does mean you’ll have a harder time keeping or improving your social level, which, it must be said, is pretty much your sole objective in this game.”

“Oh. How do I keep my status?”

“Well, the first thing you need to do is spend a certain amount of money every month. Since you’ve got such a high status, you’ll need to pay a lot. How much is your monthly income?”

“I rolled ‘impoverished,’ so…nothing.”

“Well, that’s not ideal. The other thing you’ll need to do is gain a certain amount of status points per month.”

“How do I do that?”

“Mostly by spending money. You don’t get any allowance? How much are you starting with?”

“A hundred crowns.”

“Yeesh. Well, the rules do state you can take out loans from other players…okay, before you guys put your hands up, you should all know that you can’t charge interest. However, if the debtor fails to pay within three months, you do have the authority to enlist them involuntarily in one of the Frontier Regiments, whereupon they will remain on campaign…”

“What is this game!?”

Good question.

The Thrust of Play

“Ready to begin?” I say; they are. “Let’s start the game on, say, May 1st. First, you’ll all declare your actions…”

“Wait, where are we? Are we already dueling?”

“No, not your actions in a scene. Your actions for the entire next month.” I pass over a cheat sheet I’d prepared. “Basically, you’ll do four things in that time. Hopefully they’ll give you enough status points to keep or progress your social level before the month rolls over and it all resets. The most common actions are as follows: go to your club, go as a guest to somebody else’s club, go to a bawdyhouse, slowly train your fencing ability, or try to court one of these mistresses I’m randomly generating…”

“Is there an actual courting mechanic?”

Of course there is. “It costs a lot of money to try and you can succeed or fail. If you succeed, you get the mistress as long as you keep her lifestyle costs covered and gain status points proportional to how awesome she is.”

“So…”

“Women are literally resources in this game, yes. A sharply limited resource. This campaign has four significant women in total.”

“Like one for each of us?”

“I guess technically. Some are objectively better than others, and also a few have special benefits, so…you’re just gonna fight over, like, the best two of them.” I weigh an ambiguity. “Actually a mistress can have more than one suitor, but if you find out about each other you’re supposed to duel. Like, you really will have to.”

“How does dueling work again?”

“We’ll…get to that. If it comes up.” Which I’m certain it will, as long as they don’t see the handouts first.

My other, gentler handouts are perused. The more strategy-minded players quickly discover that their lower-status characters can reap insane amounts of social cred by toadying along to Hunter’s with the viscount’s bastard. This goes a long way towards solving said bastard’s financial woes, as there is expressly no rule against charging a toadying fee.

The month of actions passes with surprising briskness, giving the broadness and minutia of the game’s mechanics. Each individual activity has its own rule or roll, but usually just one roll with complex modifiers and results. Not counting the initial rules explanations, a month of gambling, carousing, wooing, and peacocking unfolds in about ten minutes.

As we go along, there’s quite a lot of discussions about mechanics and strategy around the table. There are also quite a few jokes about the story the dice rolls are telling about their characters. There is not, however, any in-character narration or thought. The heads-down, complex, and clerical nature of the game seems to discourage scenes from unfolding organically.

We can’t know for sure, but considering the rules only halfheartedly suggest naming your character, this is probably how the game was often played. En Garde! self-applies the label “simulation,” which in 1975 had a lot more currency than “roleplaying game,” but even today I think it’s a fair categorization. The game surely has more in common with Oregon Trail and Princess Maker than Eye of the Beholder or Final Fantasy.

The game holds the group’s attention. It helps that everyone is resolving actions simultaneously, but the game is not unenjoyable. It’s very much like we’re playing an amusing and very unfair board game drawn from someone’s closet.

Especially when a duel to the death breaks out.

This is, of course, inevitable; the game is not called Relax! The rules make it clear that the only thing that louche French aristocrats love more than gambling and buying street cred is finding reasons to skewer one another.

Characters will never face consequences for challenging a romantic rival, a member of a rival regiment, or a commoner in a high-class club. If a fight breaks out for any other reason, it falls to the rest of the players to vote on whether satisfaction is called for or the challenge is frivolous.

The cause of our first duel to the death is “we feel like it.” It receives a nod of approval from the ad-hoc committee of chivalry.

“So I got good news and bad news,” I announce as I thumb through my printouts. “The good news is, I have multiple copies of the dueling references.”

“What’s the bad news?”

I spread them out. The players incline their necks a few degrees and—in the blinding matricies of symbols and numerals—see the unsympathetic face of a long-dead god.

“If we just assume you’ve both got standard rapiers,” I break in after a moment, “we can skip this table and most of this section here.”

This meets no objections. “So how many dice are we going to need for this?”

“Surprisingly? Between one and none at all. This game’s a rarity in that combat has no central element of randomness. You only have to roll dice if you miss an attack so badly that you risk breaking your weapon…or if you try to throw your sword, I guess.”

“Throw your sword?”

“Yeah. You hit one in six times.”

“And then what do we do for the rest of the duel?”

“That’s between you and the Marquess of Queensberry. I haven’t actually lurked any En Garde! MLG strategy boards, but I personally recommend you don’t discard your sword in mid swordfight.” I pass out scratch paper. “You will need these.”

“To record damage?”

“No, your next twelve combat actions.” As they listen in mute attention, I outline the bleeding edge of En Garde!

Every turn, each character will take a specific action. Lunging, parrying, resting, cutting, slashing, kicking, blocking, surrendering…there are many options. Each is cross-referenced with the other players’ move on a table which spells out the results.

The tricky part is that players don’t get to just do whatever they feel like on a given turn. They have to plan their actions out in big chunks called “sequences.” The better duelist’s first sequence is six turns long, but all other sequences are twelve at a time. A lot can happen in twelve turns.

If this wasn’t tricky enough, players can’t individually queue up whatever actions they want. Instead, actions must be taken as part of preset package deals called routines. For example, one can’t simply lunge; instead one must spend a first turn resting, a second lunging, and a third resting again. To slash one must rest, rest, and slash; to furiously slash one rests, slashes, rests, cuts, and rests thrice more. This is but a small sampling of the violent menu on offer.

The obvious analogue is to fighting game combos, a concept this game predates by about a decade, but where a combo is reactive and vital a sequence of routines is rigid and inflexible…

“…with one exception.” Eyes are glazing a bit, but I press on. “There’s three optional routines you can bust out in mid-sequence. They’re all strictly defensive, and any actions left over from interrupted sequences become rest, which is a euphemism for sitting duck. You really, really don’t want to have to rely on defense moves, so plan your turns carefully.”

“How?”

“I don’t know. Also, which of you has the lowest Expertise? You’ll need to start out with your first twelve turns planned out. You’ll also need to put in extra rest routines.”

“Because I suck?”

“That’s the thrust of it, yes. Bon chance.”

Each duelist dutifully consults the list of routines and composes a full sequence. The table falls silent as I square up the actions table and clear my throat.

“Are you both ready to read your first actions?”

The players lock canny, appraising gazes. Each nods crisply, cupping their hand over their sequences. You could cut the tension with a saber.

“The duel begins,” I declare. “Declare your first turn actions…now!”

“Rest.” “Rest.”

“Turn two!”

“Rest.” “Parry.”

There was a moment’s pause.

“Well,” I said, “nothing’s happened so far. Turn three…”

“Lunge!” The room stirs, but the player slackens. “Actually, I can only lunge if the parry was successful. So…rest.”

The other player achieves an actual lunge. I drag a finger across the page. “You Lunge…they rest…table reads damage of two.”

Pencils are raised.

“…which is multiplied by the attacker’s Strength of 18, so…defender, you lose 36 Endurance.”

The duelists choke simultaneously, palpably struck by the size of this number. Though the attacker is still unscathed, it doesn’t escape their attention that 36 damage would have been exactly half of their hit points. “What…happens when we hit zero?”

“Good question!” I review my notes. “Death. Next turn!”

The farce of parries-to-nowhere and awkward double-rests continues, but with a macabre edge. The hits that do land inevitably provoke a sucking of teeth and muttering of profanities. A handful of turns later, the underdog kicks the challenger in the chest for 39 damage and kills them stone dead in the middle of the social club. As the slain noble parcels out their life’s savings, the victor turns to their own practicalities: “How many status points did I earn today?”

“Well…” I carefully review the chapter. “Remember to mark down the two status points you gained from gambling before the duel happened. As for the duel itself…you accepted the challenge, risked your neck, and honorably killed an aristocrat in a duel to the death, so you gain…” I double-checked my math. “Two status points.”

I let the silence sour.

There are no more duels that session. In a very real sense, the session is now over, for we have no new mechanics and outcomes to explore. Not because the system is nothing but romance, carousing, and dueling; actually, that’s barely half of it. It’s just those were the only mechanics I managed to understand, and not for lack of trying.

You’re in the Army Now

One option for an up-and-coming character is to buy an officer’s commission from the most prestigious regiment that will have you. The post may or may not convey any actual responsibilities, but the important thing is that you get a sharp uniform, a status boost, and something to do on weekends. Signing up is easy for a player character. For the player, it involves learning about 60% of everything there is to know about 17th-century military bureaucracy.

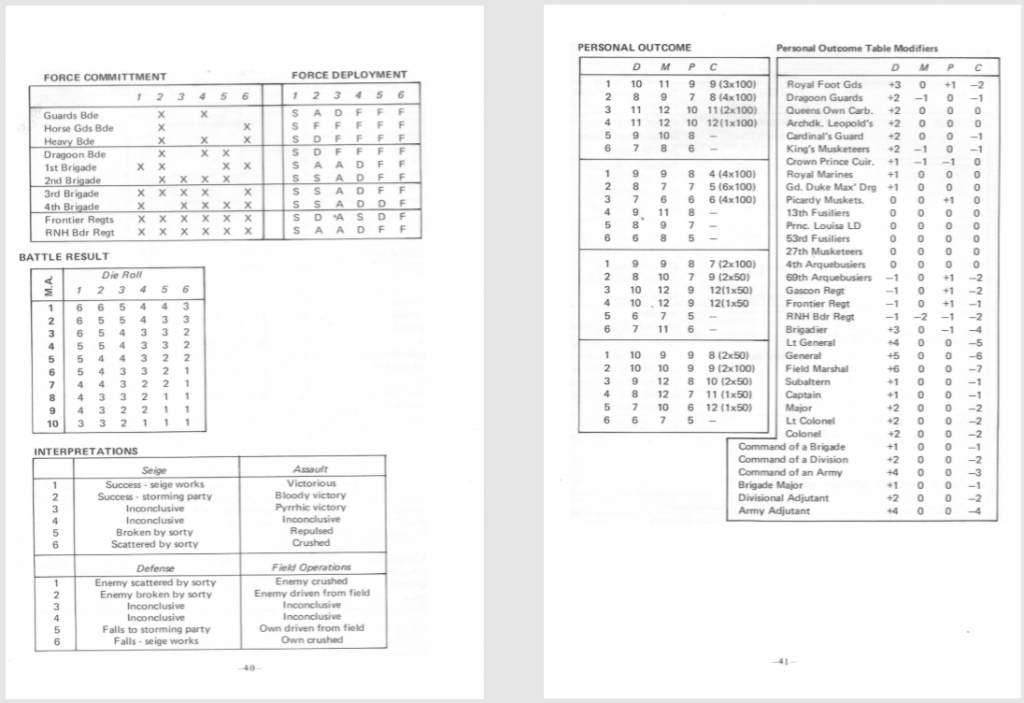

I am not going to explain these mechanics. What I will do is provide a few excerpts from the actual rulebook. You may find yourself skimming them. That is completely fine. Unless, of course, you actually mean to play this game; in that case, you’ll need to understand this in minute detail.

…each infantry regiment has three battalions, numbered one through three. Each battalion has two companies, for a total of six per regiment…

…there are ten officers about the rank of Subaltern in each regiment; there are an unlimited number of Subalterns and privates for the purposes of this game. Upon joining a regiment, each player should make a chart…

…since promotion is only possible if there is an opening available, players will want to keep a record of the fate of the other officers in their regiment, whether they are player characters are not…

…therefore, the Captain commanding A troop is the senior captain of the regiment. Since the Colonel’s military ability (M.A.–explained in later rules) is important, roll one die upon enlisting…

…a player from each regiment should roll once each game year to determine if one of the two majors is serving as a Brigade Major (see Military Appointments Table and Appointment rules). On a roll of 1 through 3, the Brigade Major is from the first named regiment of the brigade…

…in the Guards Brigade, the Brigade Major is from the Royal Foot Guard on a roll of 1 or 2…

…The Lieutenant Colonel is now the acting regimental commander, since the Colonel has been promoted to Brigadier General and now serves elsewhere (see Brevet Rank). Notice that this does not open a position of Colonel in the regiment, since his permanent rank is still…

…at the conclusion of each battle where there is a Captain’s vacancy, roll two dice on the Personal Outcome Table to see if a Subaltern is promoted into that slot…

This is probably a good time to remind people that tabletop gaming in 1975 was largely if not entirely the remit of historical wargamers, and that there’s a nonzero chance these passages were proofread beneath the brim of a shako.

So let’s say you get your head around all that. Great! That was the background reading. Now that you’re up to speed, you’re ready to learn how military campaigns actually work.

En Garde! makes a pretty clear distinction between joining the army as a form of networking and enlisting with the aim of actually fighting something. That said, anyone who’s joined the military might accidentally find themselves on campaign. When that happens, you can just about forget all that stuff about mistresses, clubs, duels, and gambling, because you’re now playing a completely different tabletop game from everyone else at the table.

To determine how well your particular squadron is doing, you must simulate the entire war. Rolls are made and cross-referenced for all layers of leadership straight down from the top, each of which has a cumulative effect on how well your final battle results go. Depending on wholly random outcomes, you might die, get rich, get mentioned in dispatches home, gain experience…

You know what? See for yourself.

From my experience with En Garde!‘s other blood-chillingly roundabout resolution mechanics, I’d guess this isn’t quite as hairy as it looks once you get your head around it. I haven’t gotten my head around it.

As best as I can figure there’s three potential advantages to being in the military: you might get money from winning battles, you might get a sort of salary of status points from fluke “good” results, and if the seventeen glorious planets of Ir-Galesh align and an officer directly above you contrives to get himself killed first, you might just be promoted. All of these are balanced against the basically constant presence of death, which is itself balanced by a “poltroonery” mechanic that lets you trade the risk of being shot for the risk of being shamed or drummed out.

Plus, when you’re in town you get to start shit with people wearing the wrong hat. Just be sure to double-check this chart first.

I’ve read quite a few novels from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Many were published serially by authors that were—not to put too fine a point on it—literally paid by the word. It was probably no accident they wrote so many passages where nothing that could be scrupulously defined as “plot” would happen. Instead there would be a journalesque dry accounting of business ventures, debts owed, habits developed and then lost, mild reputations established and shaken, modest accomplishments and unimpressive failures. In this sense, and only this sense, does En Garde! emulate its literary inspirations. If Errol Flynn was ever in a movie like this, I must have fallen asleep. The system simply does not lend itself to the swashing of buckles, and if you want a classic system for rapiers and sparkling wit, you needn’t look past 7th Sea to this musty long-neglected chapbook.

But the game does lend itself to what its creators could hardly predict would be a long-lasting and ever underserved niche of gaming: asynchronous play.

Consider the gaming scene of 1975: a rare, shy breed spread thin across many miles of country. Just enough members to maintain a few very broad non-gaming national publications and a lot of small shabby ones cranked off college presses. Even if you were lucky enough to get in with the cool kids on the ground floor of Dungeons and Dragons, the first time your job moves states—that’s it. Game over. Unless you’d like to rack up a king-hell phone bill telecommuting your magic user from Akron, your mechanical storytelling itch will likely remain unscratched.

But what if there was a tabletop game you could play without needing to walk, drive, or bus a group of like-minded nerds to the same table? One you could play even after you graduate, have kids, and move six states over from any of your acquaintances that know what a guisarme is? One where you could extrapolate not just your next in-character action, but your next month’s worth of actions, and fit them all on one postcard?

Now is as good a time as any to tell you that En Garde! would run through three more editions. I have legally purchased from the rights-holders my very own .pdf of its most recent iteration; to put it very mildly, not much changed in thirty years. To put it less mildly, I can’t actually find any changes. Doubtless I’d spot some if I laid the books side-by-side, or were more fluent in the game’s bespoke military bureaucracy, but to my moderately-initiated eyes it seems rather like the old ruleset with modern pagesetting software and some anachronistic cartoons. The fandom has clearly filed the game under ain’t broke.

I don’t say fandom lightly. Like many dusty games from the nomad days of the hobby, En Garde! is still regularly played today. Quite unlike those games, it’s played by new players; players, in fact, who were not yet born when the game’s first, second, or even third editions were released. This is because for all its flaws, En Garde! makes for a celebrated forum-style play-by-post game.

Even in the 1980s it was not lost on enterprising nerds that En Garde!’s deterministic nature, factored in with the accelerated number-crunching capability of personal computers, offered a brand new kind of gaming opportunity. GMs could automate the dice-rolling and book-keeping on their systems and run vast fifty-player games at conventions, evidently using small teams of referees to process the vast volumes of “orders” coming in from players. And as in all things, what can be done live in a poorly-ventilated convention center in 1983 can be accomplished as well over a relaxed schedule on a Macbook in 2018. Or—if we’re being demographically realistic—a home-built laptop running Ubuntu.

There are currently-running En Garde! games to satisfy all tastes and temperaments. Users generally submit actions by e-mail or forum post and are notified of developments in lavishly-narrated reports that affect the style of period novels or society papers. A Patreon backer of mine was kind enough to share dispatches from a former campaign; the length of the reports are matched only by the effort and detail put into the narration, doubly impressive when one considers how numbingly repetitive actions must become in large-scale games of En Garde! To its many hard-working disciples, I offer nothing but respect.

If you’d like to dip your toe in the history or modernity of the fandom, you can begin by visiting the official website here.

This post was originally run as an early-access Patreon series. After a year, it has been reproduced here.

The illustrations from this post are from the 17th century artist Jacques Callot, collected by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A gallery of his work may be viewed here:

https://collections.lacma.org/node/154911

Nifty… I not only will never play this game but will likely never recommend it to anyone regardless of their rpg preferences. I am seriously baffled at how such a convoluted creation came into being, this is like checking Dr Frankenstein’s notes and seeing that he’s building a man only to look up and see that somewhere in the design process the creature has become some lovecraftian horror whose origins are as inexplicable as the mind the birthed it.

I am but an amatuer, and it’s not quite my period, but those descriptions of regimental organisation etc. sound very legit. Rolling to find out which Major is the Brigade Major is first rate.

(Organisations above the level of regiment were ad hoc at the time so whoever was in charge of a brigade would assemble a staff from officers in the regiments in the brigade, plus some of their own hangers on; the Brigade Major was the chief of staff)

I love that you are breaking open these historical artifacts of the hobby! Keep ’em coming!

I got my hands on a copy of the revised edition back in the day. The owner of my FLGS pointed to it and suggested that I might like it. It remains one of my most prized possessions to this day.

The combat system is really quite elegant. When I first got it, my best friend and I had a bunch of duels, and strategy was clearly at play. You could generally react to the other player in the first few turns of your sequence, but you’d have to be tricky with the last six turns, to try and throw your opponent off what you wanted to do. So, nothing was quite so scary as hearing “close” because you knew it would be followed up by “kick” and there was nothing you could do about it.

I also really dig the character creation (for pretty much the same reasons that I really dig Traveller’s character creation, not surprising that they were both GDW games). When you lay down the plot of a character’s story, outside of the hands of the player, the player gets to fill in all the colour to the story. It really gives a background some meat for its bones.

As a side note, the Top Secret rules (a TSR spy RPG) had a similar system for unarmed combat, though much simplified — you didn’t have to plan moves ahead of time, just compare move against move.

Ridiculous crunch aside, this game sounds awesome! A more streamlined version of this could be a really cool game, or a cool sub-system in another game. Also, this was an excellent writeup!

En Garde! is not a artefact it’s a living game widely played my email nowadays.

In many different milieus over the years from Rome to Arrakis to the Napoleonic Royal Navy and Army to Pirates to John Carter!

I play in Paul Evans LPBS game as ZUT (Zavier ulric Turenne) Brevet Brigadier General and Colonel of The Picardy Musketeers.

fine and loyal applicants to the regiment always welcome

I first played this game at European Gen con 92. Room full of people waiting for the next post of results! It was a fun experience to which I now run my own game through Discord called “Sword and Crown”.

The unintended genius of this game is that it’s easy to modify or add to. It wasn’t a stretch to create male courtiers in addition or the female courtesans. Allowing males and females to be in regiments either.

As opposed to 4-6 hours huddled in a basement playing an RPG, this is an easy one that you can play without giving up huge chunks of time.